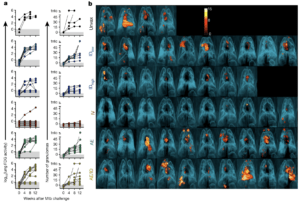

Protection against Mtb infection after IV BCG immunization. a, Lung inflammation (total FDG activity) and number of lung granulomas over the course of infection as measured by serial PET–CT scans. Each line shows one NHP over time; 3 NHPs (2 unvaccinated (unvax) and 1 IDlow) reached a humane end point before 12 weeks. tntc, too numerous to count. b, Three-dimensional volume renderings of PET–CT scans of each NHP at the time of necropsy. PET was limited to the thoracic cavity; the standardized uptake value colour bar is shown in the top right and indicates FDG retention, a surrogate for inflammation. (Source Darrah et al., 2020)

Almost 100 years since the development of Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, it is still the only licenced vaccine against Tuberculosis (TB). BCG is predominantly given to infants, where it provides protection against disseminated TB in children but has very variable efficacy against TB in adolescents and adults.

TB vaccinologists suggest that reduced efficacy in adults could be partly due to the route of BCG delivery. Where intradermal BCG vaccination, predominant route of delivery, does not induce sufficient long-term lung-resident memory responses. In line with this, animal TB models have demonstrated better survival post-Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) challenge following aerosol or intravenous BCG vaccination, compared with BCG-ID vaccination.

In this article, we highlight a recently published article by Darrah et al., which aimed to determine how dose and route of BCG vaccination influence the generation of systemic and tissue-resident immunity, as well as “protect” against TB. In their study, they vaccinated non-human primates (Macaca mulatta) with one of the following strategies:

- Normal dose intradermal vaccination: IDlow

- High dose intradermal vaccination: IDhigh

- Aerosol vaccination (AE)

- Intravenous vaccination (IV)

- Combination of IDlow and AE

Darrah et al., showed that BCG-IV resulted in superior T cell and antigen-presenting cell recruitment to the lung compared to other vaccination strategies. In addition to T cell and innate immunity, BCG-IV also induced superior vaccine-induced antibody responses. Following M.tb challenge, the BCG-IV cohort consistently has the lowest bacterial burden with 6 out of 10 NHPs with undetectable bacterial burden and 9 out 10 protected from TB. In addition to the low M.tb burden, BCG-IV was the only vaccination strategy that did not result in an increase of Mycobacterial-specific T cell immune responses post M.tb infection. Based on these results, one of the proposed mechanisms of BCG-IV protection is due to the induction of robust systemic and lung resident T cell immunity, which sufficiently controls and eliminates M.tb burden.

In summary, Darrah et al., showed that BCG-IV confers superior protection against M.tb infection. Thus providing sufficient evidence for clinical testing BCG-IV vaccination to prevent M.tb infection and TB.

Journal Article: Darrah et al., 2020. Prevention of tuberculosis in macaques after intravenous BCG immunization. Nature