Malaria continues to claim hundreds of thousands of lives each year with the majority occurring among young children in sub-Saharan Africa. Traditional methods like insecticides and malaria vaccines face significant hurdles, such as growing mosquito resistance and limited vaccine efficacy.

A newly identified weakness in Anopheles mosquitoes—the species responsible for most malaria transmissions worldwide—could pave the way for more effective malaria control, according to new research (Figure 1). The study highlights a molecular quality-control system in mosquitoes that could be exploited to stop the spread of malaria.

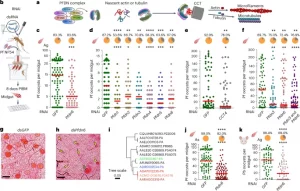

Figure 1: PFDN6 serves as a host factor for multiple malaria parasite species in multiple Anopheles species, and functions as a component of a heterohexameric protein complex known as PFDN–CCT/TRiC. a, PFDN–CCT/TRiC complex: six subunits of PFDN (with two alpha types (that is, PFDN3 and PFDN5 in blue) and four beta types (PFDN6 and PFDN1, PFDN2 and PFDN4, with corresponding colour codes)). The PFDN protein complex delivers nascent actin and tubulin to CCT/TriC for the assembly of microtubules and microfilaments. b, RNAi-mediated gene silencing process and subsequent P. falciparum (Pf) infection assay. PIBM, post-infectious blood meal. c, P. falciparum oocyst-stage infection prevalence and intensity in A. gambiae (Ag) midguts after silencing of Pfdn6 compared with the Gfp-RNAi control at 8 dpi. d,e, Significant decrease in P. falciparum oocyst loads after silencing each subunit of PFDN (d) and CCT subunit 4 (CCT4) (e). Detailed sequence alignments of Pfdn subunits and CCT4 are listed in Supplementary Data 2 and 3. f, Co-silencing of PFDN complex subunit genes pfdn6 and pfdn3 shows no additive effect on mosquito permissiveness to P. falciparum oocyst-stage infection. g,h, Representative microscopic images of mercurochrome staining of midguts with mature large oocysts in the control Gfp dsRNA-injected group (g) and small oocysts (h, yellow arrows; green arrow, mature large oocyst). n = 20; scale bars, 75 µm. i, Phylogenetic tree of PFDN6 in various mosquito species with the nodes of A. gambiae (red), A. stephensi (green) and A. dirus (blue) and others (sequence alignment details in Supplementary Data 1). j,k, P. falciparum oocyst-stage infection prevalence and intensity in the midgut of A. stephensi (As) at 8 dpi (j) and P. berghei infection in A. gambiae mosquitoes at 12 dpi (k). Each dot represents oocyst numbers in an individual mosquito (c–f,j,k), and the red line indicates the median. The small pie charts show infection prevalence. At least three replicates were included, and statistical significance was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test (two tailed) for infection intensity and Fisher’s exact test for infection prevalence. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Detailed statistical analysis and P values are provided in Supplementary Table 2. Panel b created with BioRender.com.

At the centre of this discovery is a protein quality-control system called the prefoldin chaperonin system, which ensures proteins fold properly within cells. The researchers found this system is essential for malaria parasites to survive and develop inside Anopheles mosquitoes.

Disrupting the prefoldin chaperonin system:

- Greatly reduced the mosquitoes’ ability to host and transmit malaria parasites.

- Caused about 60% of the mosquitoes to die in laboratory experiments.

What makes this finding especially promising is that the prefoldin system is consistent across Anopheles species, meaning this strategy could be effective in all major malaria-endemic regions worldwide. This discovery introduces a novel angle: rather than focusing solely on killing parasites or mosquitoes, the team has identified a way to disrupt the mosquito’s biology itself—potentially with minimal risk of resistance development.

The researchers used gene-silencing techniques to block activity in the Pfdn6 gene, a component of the prefoldin complex in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Silencing this gene not only prevented the parasites from completing their life cycle but also triggered a deadly reaction in the mosquitoes:

- The disrupted prefoldin system caused the mosquitoes to develop a “leaky gut.”

- Gut microbes escaped into the bloodstream, causing systemic infection and an overwhelming inflammatory response.

- As a result, 60% of the mosquitoes died—dramatically reducing their ability to spread malaria.

The discovery of the prefoldin chaperonin system’s role in malaria transmission introduces a radically different strategy in the fight against one of the world’s most devastating diseases. Rather than focusing only on the parasite, scientists are turning the mosquitoes’ own biology against them.

This breakthrough may represent a paradigm shift in malaria control, offering hope for more effective and durable solutions in the global fight against the disease.

Journal article: Dong, Y., et al. 2025. Targeting the mosquito prefoldin–chaperonin complex blocks Plasmodium transmission. Nature Microbiology.

Summary by Stefan Botha